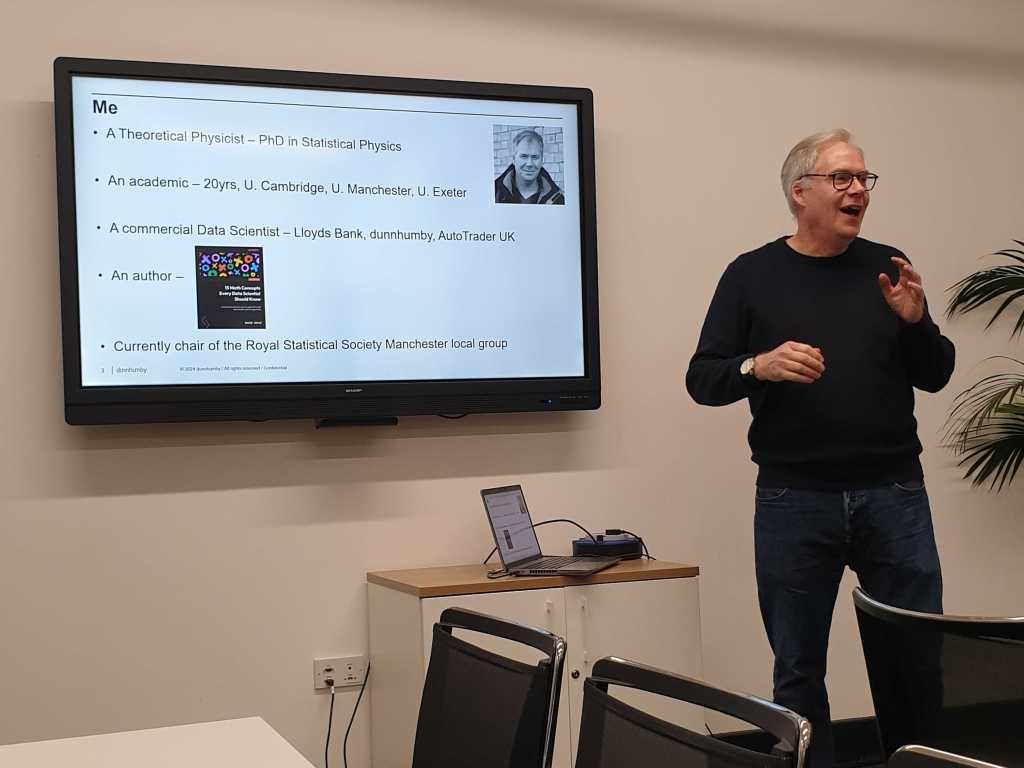

Dr David Hoyle’s presentation at the MSS AI Study Group Meeting in January 2025 focused on the concept of demand modelling in grocery retail, explaining its significance and the methods used to forecast sales.

The presentation highlighted the importance of analytics in grocery retail, emphasizing that the business model, characterized by low-profit margins and large-scale operations, benefits significantly from data-driven decision-making. Small improvements in the supply chain or offering can lead to substantial gains. Retail analytics thrives due to data richness, large scale, and the clarity of its objectives, particularly in demand modelling, which focuses on managing the supply chain and optimizing product offerings based on consumer demand.

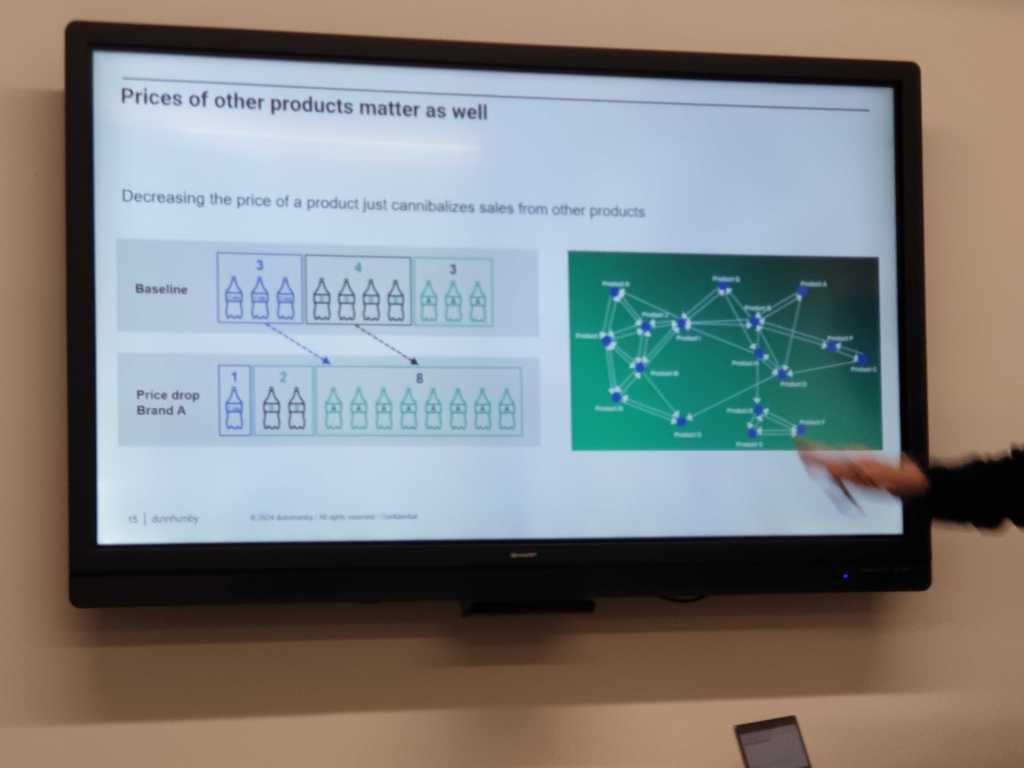

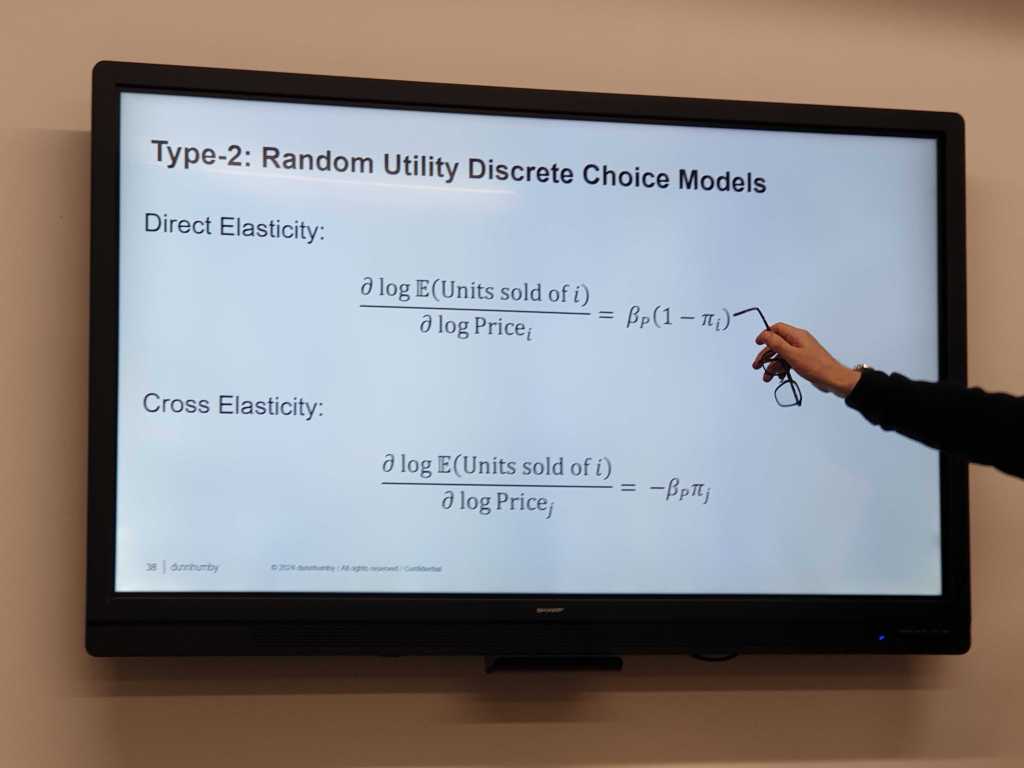

A demand model is designed to forecast how much of a product will be sold, considering inputs such as price, the prices of other products, promotions, and seasonal factors. The basic relationship between price and demand follows a predictable pattern: lower prices generally result in higher sales, while higher prices lead to reduced demand. This relationship is captured by the concept of direct price elasticity, which measures the percentage change in units sold relative to a percentage change in price. Cross-price elasticity, which examines the effect of changes in the price of one product on the demand for another product, is also important, especially for substitute goods.

Operational challenges in demand modelling arise from the vast number of products, price zones, and customer segments that need to be considered. For large retailers, this can mean handling 500,000 to 1 million models, each requiring constant updates based on the most recent customer behaviour. Models must be built frequently, often on a four-hour cycle, and they must deliver credible, transparent, and actionable insights even when data quality is poor. Data feeds from transaction systems must be accurate and up-to-date to prevent model failure, as any breakdown in the models can have significant operational consequences.

To address these challenges, Dr Hoyle suggested incorporating econometric principles into demand models and keeping the models simple to ensure they remain robust. Additionally, techniques like hard pooling (using the same parameters across different product groups) or soft pooling (using Bayesian priors) can help address data-related challenges by making the models more flexible and adaptable.

Dr Hoyle concluded by discussing two broad types of demand models: Type-1, which aggregates sales data to model total units sold over a period, and Type-2, which models the customer decision-making process, focusing on the probability of purchasing a particular product from a selection of competing options. Type-1 models are typically simpler and rely on classical econometric approaches, while Type-2 models, such as random utility discrete choice models, are more complex and focus on individual consumer preferences.

In summary, demand models in retail offer clear benefits, but they must be reliable, simple, and grounded in economic principles. While more complex machine learning models may play a supporting role, the core demand models remain grounded in microeconomic behaviour to provide actionable insights.